The Savannahian featured this excerpted piece by Community Organizer Luis Zaldivar on February 15, 2021. Read the full version at The Savannahian.

I have been active on progressive advocacy issues for many years. Since I arrived in Savannah in the middle of 2020, criminal justice reform has been at the forefront of my activism. I have had multiple conversations with leaders, read the books and articles, and most importantly listened a lot. Here is where I come from and what I have learned.

Having been raised in South America, my experience with the police has been different than that of Americans. Back in Peru, the total budget for policing and national defense of 2020 was only 3% of total expenditures. Encounters with the police were rare and the general perception about them was that they are corrupt to their core, so you can’t really count on them for anything.

Instead, neighborhoods and communities around the country have traditionally organized their own forms of security. In my neighborhood, it took the form of serenazgo, folks paid directly by the neighborhood associations to keep away any trouble. Growing up, I became very fond of my local serenazgo, who would deal with the occasional addicts that would roam the area trying to score anything they could sell. Most of them were mature men who had rough lives themselves in the streets and found in serenazgo the perfect place to use their particular skill set.

Up until today, this form of civilian safety patrol is the most common and direct interaction people have on a daily basis with a public safety official. So when I hear of terms like “reimagining policing” or “community model of public safety,” I don’t think of them as naive progressive ideas. I’ve lived them, and I know they can work.

However, in the past 20 years, the increasing number of fire weapons available in the streets of Peru has made serenazgo insufficient to keep safety in some of our communities. My neighborhood, which was already seen as a somewhat difficult area, is now no longer safe to walk after a certain time of night. Many neighborhoods have opted for placing security fences. Sometimes it no longer feels like the place I grew up.

I have also been in places where the police have been, for all intents and purposes, abolished. In 2013, I spent weeks working on a project in the valley of the rivers Ene and Apurímac (known as VRAE) in the region of Ayacucho. This is an area where, for the past few decades, there has been a standoff between drug cartels and the military for control. When I crossed the border, I was under the surveillance of the former and there was no police presence. I kid you not, this is one of the places where I have felt the safest walking around.

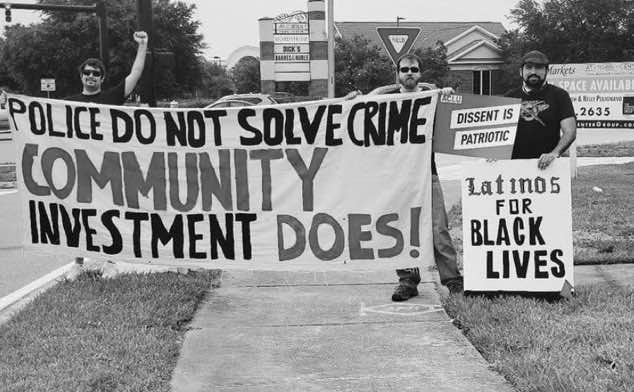

Zaldivar at a Black Lives Matter march in summer of 2020.

However, weeks after I left, I learned an internal dispute had left many people dead in an indigenous community I worked with. Because of lack of coordination between the de facto authorities that control the territory and the outside ones, people died due to lack of medical treatment.

I also spent months working in Andean communities where justice is still delivered through rondas campesinas, civilian corps that gained prominence in the fight of indigenous people against the insurgency of the Shining Path in the ’80s. Now, in times of peace, the ronderos simply decide on the number of whips people should get for defying local rules, or to work for free on some community project as punishment.

To continue reading the full version, visit The Savannhian.com