This blog post, written by Program Manager Maria Zoccola, is the second in an ongoing series, 10 Years Deep, that celebrates the evolution and growth of Deep Center’s programs in our first decade.

(Read all posts in the 10 Years Deep series here.)

At Deep, we use creative writing and the arts to help young people connect their learning to their lives, their lives to their communities, and their actions to positive change. Deep learning is connected learning that nurtures creativity, play, and building power in the world. We make learning purposeful, personal, and truthful by embedding it in the neighborhoods we come from and the stories of the people living there. And because Savannah’s young people deserve to be honored and heard and cared for, in our first decade we have become more and more intentional about encouraging them to write and talk about the “big stuff.”

Big Stuff

Hubert Middle School’s Room 170 is buzzing. Ten or 12 middle schoolers are clustered around the central table, all clamoring to read out loud the ideas they’ve just finished writing on the board.

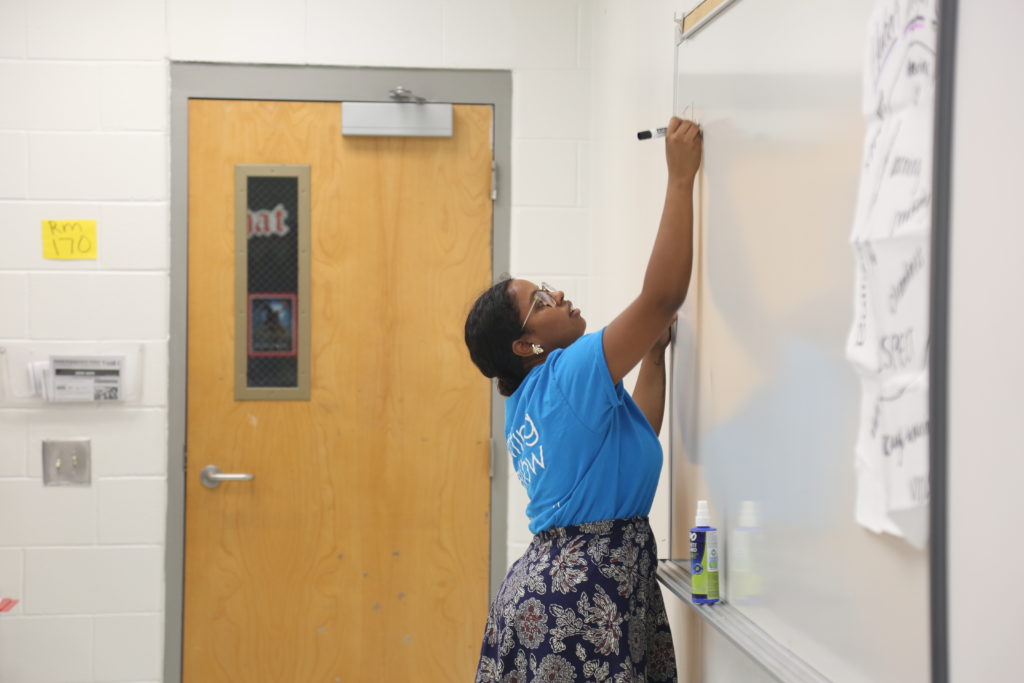

Deep Writing Fellow Asli Shebe

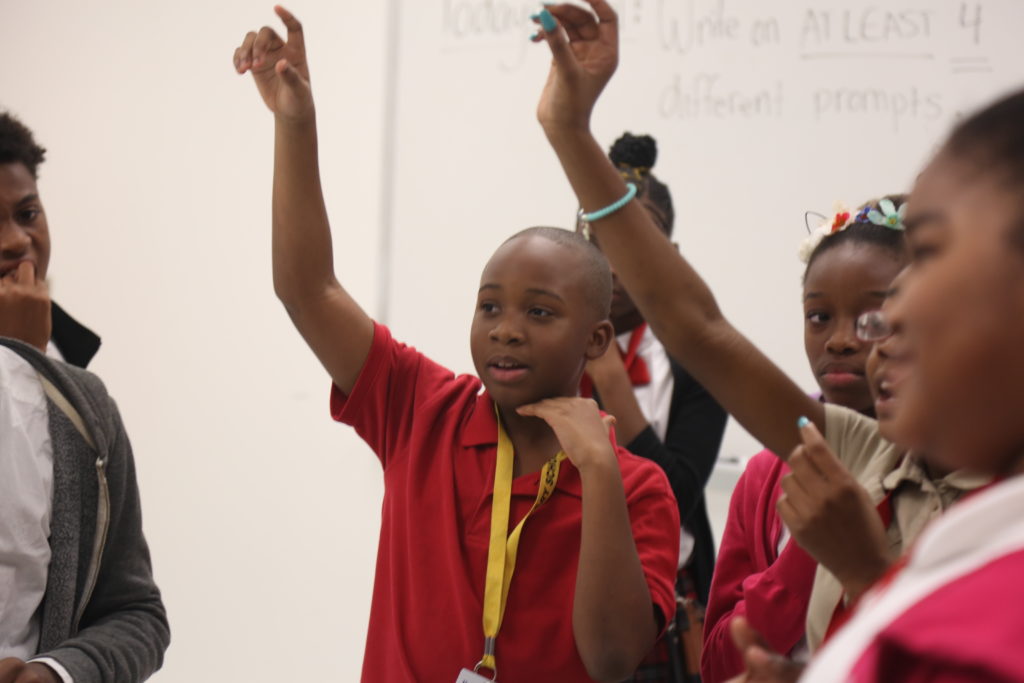

“Wait, wait, wait,” says the workshop leader, Asli Shebe. “One at a time! Remember our Target Circle.” She points to a big sheet of paper hung on the wall. A circle is drawn on it. Outside the circle are words like “bullying” and “giving up” and “yelling.” Inside the circle: “curiosity,” “creativity,” and “respect.” Asli underlines the word “respect” with her finger, and the room settles down. Hands are thrown in the air. “Yes, Lan’Drea. What did you write on the board?”

“Um, I wrote, ‘girls getting kidnapped.’”

“Thank you for writing that,” Asli says. “Let’s talk about it.”

The whiteboard behind Asli is covered with writing. Elbowing each other for space, the young people in the Hubert workshop just spent five minutes compiling an extensive list of the “Big Stuff” that’s going on at their school, in their neighborhoods, in their city, in the state of Georgia, in the South, in America, and in the world. Asli gives them no limits. If they know about it, if they’ve heard the adults in their lives talking about it, if they are thinking about it, up it goes on the board. Positive or negative, plus or minus, good or bad.

At the end of those five minutes, the board in Room 170 is jam-packed with bad.

This is not unexpected. Deep Center’s Young Author Project (YAP) has spent ten years creating spaces for Savannah’s middle schoolers to write bravely and honestly about their lives, their worlds, and their futures. Over the summer of 2018, Deep redesigned the YAP curriculum to more directly and explicitly engage with real-world issues concerning our youth–issues like violence and racism. This particular workshop at Hubert Middle resulted from the new curriculum, from a unit called “Current Events.” Our reasoning behind the evolution is simple: it’s been a hard few years for us here in Savannah, Georgia.

A Hard Few Years

It’s been a hard few years for us here in the United States, in fact. For us here on planet Earth. The political climate is suffocating, and each week seems to bring a new wave of domestic terrorism. Poverty has the American South in its grip, and across the nation, white supremacist and fascist groups are growing louder. For under-resourced, mostly-black Hubert Middle School, oppression is not a concept but a reality, a heavy hand pressing down on the back of each young person, even the 11-year-olds. Especially the 11-year-olds, who feel that weight every single day but are never allowed the agency to confront it head-on. But in YAP, agency is not just allowed, it is understood as fundamental. Through pen and paper, our middle schoolers speak truth to power in a world that feels darker with every passing day.

Eager to have their say

Lan’Drea wrote on the board that girls were being kidnapped. Makaylah scrawled “RAPE” in capital letters. Antonio speculated that World War III was approaching. Faith commented on the climbing levels of homelessness. Habana wrote about how many people were committing suicide. Joshua wrote that he needed five dollars and also that there were too many guns. And Romon wrote that police were killing black men.

“Thank you for writing that, Romon,” Asli says. “Let’s talk about it.”

Voice by Voice

And in Room 170, the Hubert writers do talk about it. They talk and they talk and they talk some more. Asli slowly pulls up a chair to the table. She’s holding a folder full of the next part of the workshop—newspaper clippings for the writers to cut and paste—but she slides the folder under her chair. There’s passion in the room, and grief, and anger, and frustration, and this discussion is so much more important than anything she’d planned for the rest of the day. Piece by piece, voice by voice, Asli spends the next twenty minutes facilitating a roundtable discussion on police brutality, which evolves into a discussion of gun violence, which evolves into a discussion about the media, which evolves into a discussion of the barbershop where Ahmad’s cousin was shot 24 hours before today’s workshop. Ahmad was working inside the shop. Habana was walking by across the street. Faith lives next door. In the Hubert workshop, Ahmad describes for us the sound of the gunshots, how everyone inside the barbershop ducked and ran for the back.

“And is your cousin okay?” Asli asks.

“He’s in the hospital,” Ahmad says. He says this while staring down at the tabletop in front of him.

“I’m so glad,” Asli says. “How were you feeling when this happened, Ahmad?”

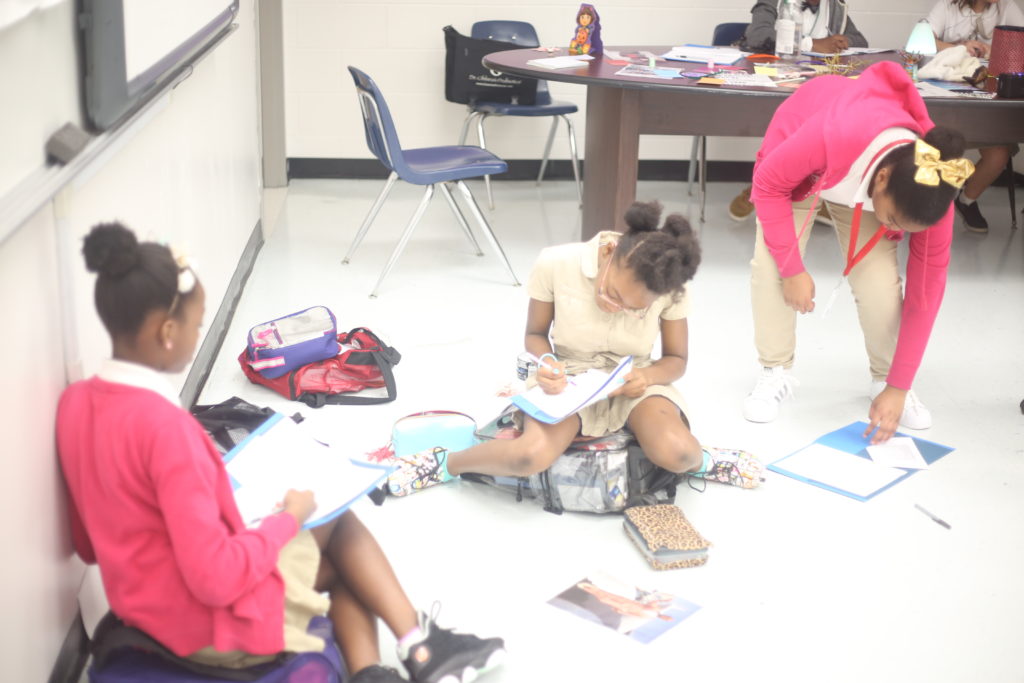

A multimedia approach to writing at Hubert

Asli’s questions are big and open-ended, gentle and curious. The discussion is fierce and powerful and noisy. Asli pauses the conversation every two to three minutes to refer back to the word “respect” on the Target Circle, keeping the discussion focused. Romon talks about modern Nazis. Mia, the only white writer in the room, gives a passionate denouncement of racism. Joshua squares up and says, “Police think they going for a gun when they just going for the wallet. Police are not trained right.”

Pens Scratching across the Page

The discussion is still lively as Asli brings it to a close. It’s time to direct that passion onto the page. Taking up her whiteboard marker again, she writes the prompts on the board:

Write a response to one of these topics: police brutality, racism, violence. Or choose something from the lists we made on the board to write about.

There’s nothing but the sound of pens scratching furiously across the page for the next 25 minutes. Asli comes around with cups of popcorn for everyone to munch while they work. Sometimes writers get stuck, and then Asli crouches down next to them to whisper about their ideas. Romon and Ahmad are ticking beats on their fingers while they write rhymes. Habana is dreaming up an end to suicide. Christiana is thinking about bullying. Everyone else is writing about racism and gun violence, and at the end of writing time, every single hand is waving in the air, madly eager to share.

Sometimes ideas flow better on the floor.

Asli invites each writer to read their work, sometimes pausing to quiet the group and underline the word “respect” with her finger. We hear short scripts and memoir pieces and fiction and poetry, and we also hear rap. There are three celebrity rappers in the workshop: Ahmad, Antonio, and Romon. They dazzle their peers week after week, producing new lyrics each workshop without fail. Today there is a collective held breath as each of the boys launches into a dizzying spiral of rhymes and jokes and figurative language and battle cries. The entire workshop is deeply aware that we are experiencing greatness, small miracles worked from the brains of 11-year-old black boys. Asli’s eyes are wet.

Romon’s rap in particular is deeply moving. Romon rails against police brutality and spends two pages tracking African-American history from the Emancipation Proclamation to Thurgood Marshal to MLK to the present day. Why, he asks, do things still look so bleak? Haven’t his people fought long and hard enough? The opening of Romon’s rap looks like this:

Police brutality, this is real reality,

people getting fatalitied. It’s a shame.

When you shoot a man and all respect is gone,

I mean, you tell him to do something

then pull the trigger—boom.

The world is broken. I know I’m outspoken,

but families’ hearts used to be open,

but now their heart and love has gone.

I mean it’s now or never. We need change.

Romon fills two full pages with lyrics. He has another full notebook at home, packed page after page with rap poetry. He is an artist. He is a creator. He is powerful, wildly powerful. Agency blooms in his hands. As he finishes his performance, Romon tosses his journal on the table in total victory. The workshop is thunderous with applause.

Head-on, Heart-forward

This is what we do at Deep Center. We look at that whiteboard chock-full of “bad” and we face it head-on, heart-forward. We take all that bad and we take all that scary and we take all that dangerous and we transform it into art. Through our art, we find agency. Through our agency, we find healing. Through our healing, we find a better world.

—by Maria Zoccola

Read all posts in the 10 Years Deep series here.